The player swats the puck over the goaltender's stick and into the net. The moment it slides across the goal line, a referee pushes a button. A red light starts flashing, and a horn sounds, signaling to everyone in the arena that a goal has been scored.

It's a familiar experience for hockey fans. And a couple of years ago, Budweiser started selling a device to bring the experience into Canadians' living rooms. The product is about the size of a roll of paper towels and has a red light and a horn. The customer picks her favorite team using a smartphone app. Then every time her team scores, the light turns on and the horn sounds, making her feel like she has rink-side seats at the game.

The Budweiser Red Light. (Electric Imp)

The $149 device has no cords. It runs for two years on a set of four D batteries. And it knows when goals are scored because it is based on a wifi-enabled computer chip called an Electric Imp. The light was one of several internet-connected gadgets I saw during a March visit to Electric Imp's Silicon Valley headquarters.

Internet-connected objects aren't new, but they're about to become a lot more common

The company's founder, Hugo Fiennes, showed me a toy pig that allows his 6-year-old daughter Chloe to record voice messages for her grandparents in the United Kingdom and get recorded responses back. There was a palm-sized kitchen gadget with a UPC scanner that lets people assemble shopping lists on the fly. And a candy dispenser that gushes M&M's every time anyone anywhere in the world tweeted the hash tag "#electricimp." Like the hockey light, these cordless products work for months on a set of standard batteries.

These devices mostly seem like toys, but they're part of a trend that could have a much bigger impact. Connecting household objects to the internet is a big Silicon Valley trend right now. Electric Imp just raised $15 million in Series B funding from a group of investors that includes Foxconn, the huge Taiwan-based consumer electronics manufacturer. Nest's internet-connected thermostat is so good that Google bought the company in January for $3.2 billion. Belkin has a line of internet-connected light switches and outlets. Philips is selling wifi lightbulbs whose color and brightness can be changed via the internet.

Internet-connected objects aren't new, but as computer chips get smaller, cheaper, and less power-hungry, they're about to become a lot more common. That could lead to big changes in how you interact with the objects around you.

The power of platforms

Every couple of decades, the plunging cost of computing power gives birth to a new kind of computing platform. The 1970s saw the introduction of the first integrated computer chips, making possible PCs that were small and cheap enough that anyone could have one on their desks. In the late 1990s, a new generation of low-power chips allowed the creation of mobile computers — smartphones — that fit in our pockets and could run all day on a single charge.

We could be at the cusp of a third computing revolution

In both cases, it took technology companies about a decade to figure out how to take full advantage of the capabilities of the new platform. PCs were clumsy niche products until the Macintosh (and later Windows) made them user-friendly starting in 1984. Smartphones didn't reach their full potential until Apple invented a modern multi-touch interface for the iPhone in 2007.

We could be at the cusp of a third computing revolution. Once again, a new generation of computer chips is dramatically smaller, cheaper, and less power-hungry than the generation that preceded it. And like PCs in 1978 or smart phones in 2001, the current generation of products seem more like toys than a technology revolution.

What's missing is software to allow consumers to manage dozens of connected devices in their homes and offices as effortlessly as we manage apps and websites today. It's likely to take several more years for the necessary technology to mature. But it when it does, it could be a big deal.

The wifi-connected candy dispenser in Electric Imp's conference room. (Electric Imp)

How connected devices will make your life better

So what might the world look like when there are tiny computers everywhere? Some of the possibilities have long been depicted in science fiction. For example, in a home where lights, heat and air conditioning, speakers, and other household equipment is all connected to the internet, systems can automatically follow family members around the home, providing convenience while saving energy.

Wifi-powered lightbulbs could turn your living room into a dance party

Multi-colored, wifi-powered lightbulbs could turn your living room into a dance party. In the bedroom, they could wake you up gently with a simulated sunrise.

Tiny chips could could mean doors that unlock when you approach them, ovens you can preheat from work (with a camera inside so you can make sure it's empty first), and sprinkler systems that check the weather online to decide whether to water the lawn today.

Connected microphones in every room could allow you to control these devices with verbal commands: "Computer, turn up the heat." "Computer, turn off all the lights in the basement."

Tiny computers could help prevent you from losing your valuables. The startup Tile is working on tiny devices that constantly communicate with your smartphone. Attach one to your keys, wallet, or other valuables and it'll always be able to tell you where you last had them.

Always connected

Connected devices could be especially helpful to the elderly. A company called SaferAging works with assisted living facilities in the Washington, DC area. Seniors might be uncomfortable with cameras or microphones in their homes. Instead, SaferAging uses less invasive sensors that detect when a resident moves or touches a kitchen appliance. When the system detects that a resident is departing from her usual routine — say, staying in bed much later than normal or spending an hour in the bathroom — it notifies a caregiver.

A SaferAging emergency button. Pushing it triggers a call to a care provider. (Safer ging)

The company's sensors are powered by Electric Imp chips. SaferAging CEO John McKinley says the chips allow his engineers to build powerful and flexible sensors with a minimum of engineering effort. And because the software can be modified remotely, the company can improve or customize the software at any time to meet clients' needs.

That's what makes internet-connected computing platforms powerful: new software can add new capabilities to hardware that's already in the field. Apple could never have anticipated all the ways people are using their iPhones. But it didn't have to, because thousands of developers did the work for them.

Once our homes are stuffed with connected devices, brainy 20-somethings will be looking for ways to make those devices more useful. The applications we haven't thought of are likely to prove even more significant than the ones we have.

The applications we haven't thought of are likely to prove even more significant than the ones we have

At this point, you might be a little creeped out. In the era of the NSA, do we really want dozens of tiny computers in our homes, many of which have cameras, microphones, and other sensors?

It's a reasonable question, but history suggests that once the technology has matured, consumers will blow past these privacy concerns and never look back. Remember that most people carry a smartphone in their pocket or purse that the government can use to track our every move and perhaps even listen in on our conversations.

Yet only a small minority of Americans have abstained from using cell phones based on these privacy concerns. Most people feel they have little to hide, and if a product is useful and comes from a company they trust, they'll have few qualms about using it.

The power of software

In the past, the key to turning new chips into a powerful, mainstream computing platforms has been to develop a user interface — mouse-based graphical interfaces for the PC, multi-touch screens for smartphones — that lets anyone use them. Connected objects will need a standard interface, too.

But it won't be practical to add a touchscreen to every lightbulb. Instead, the web itself is likely to be the interface for connected devices. Users are never going to accept a system that expects them to configure every lightbulb individually. But it should be possible for smart light bulbs to automatically log into the local wifi network and register with the app the person is using to manage smart devices in his home.

Once the hurdles of device setup and management are eliminated, smart devices could find a broad audience. A user-friendly app that allowed people to remotely turn off all the lights at home, turn down the thermostat, pre-heat the oven, activate the sprinkler system, view pictures from inside the refrigerator and oven, listen to the baby monitor, and a lot more would quickly become indispensable.

Getting there won't be easy because it will require getting a lot of devices made by different companies to talk to each other. But the company that figures out how to do it could make a ton of money.

Electric Imp

Electric Imp CEO Hugo Fiennes hopes his company will be the one that makes the next computing revolution happen. And he's well-positioned to do it. After almost a decade building MP3 players, Fiennes joined Apple in 2006 to lead the hardware team for the original iPhone.

Hugo Fiennes. (Electric Imp)

After the iPhone launched, Fiennes did work for Nest, the connected thermostat company that was founded by Apple veterans. "I was torn on whether to join Nest or not," Fiennes says.

Like Apple, Nest maintains control of the entire user experience, including hardware, software, and network services. In contrast, Fiennes believes that connected devices will only take off if a lot of different companies build connected devices. That's the vision behind Electric Imp, which he founded with two colleagues.

Four decades ago, Intel launched the PC revolution by selling computer chips that anyone could build into their own products. Eventually, there were dozens of PC brands, most of which sported "Intel Inside" stickers. Electric Imp hopes to play a similar role for the next generation of connected devices. Other companies will design and market the consumer products, but Fiennes hopes most of them will have Electric Imp chips inside.

Electric Imp chips are about the size of a postage stamp, and a new generation due out later this year will be even smaller

Electric Imp chips are about the size of a postage stamp, and a new generation due out later this year will be even smaller. The tiny package contains a computer as fast as a Pentium chip from the early 1990s and wifi capabilities for connecting to the Internet. You can buy a single Electric Imp for $25, and the company says they're available for as little as $11 each in bulk.

The chips are designed to work seamlessly with Electric Imp's servers, so that processing-intensive tasks like image manipulation or voice recognition can be done in beefy data centers where computing power and electricity are plentiful. This cloud infrastructure allows security fixes and other software updates to be pushed out to the field automatically, sparing manufacturers the headache of having to ask their customers to manually install new software.

"We don't believe in one-size-fits-all"

Electric Imp is far from the only company working on connecting objects to the internet. For several years, hobbyists have been experimenting with small, cheap computers such as the Raspberry Pi and the Arduino. Another product, called the Tessel, is slated to hit the market before summer. But these products are targeted more at tinkerers than companies building consumer products, so they're unlikely to form the foundation for mass-market consumer products.

Some established companies are also building infrastructure for what some call the "Internet of Things." One of the most active is Texas Instruments, which has a broad range of tiny, low-power chips. Whereas Electric Imp has focused on developing a single integrated platform, TI sells chips that support a wide variety of standards.

"We at TI don't believe in one-size-fits-all," says TI's Avner Goren. "Different customers, different organizations will make different tradeoffs." Some are low-power chips that only work over short ranges. Others are can communicate longer distances but consume more energy.

TI sees the home as one big market for its products, but Goren stresses that connected devices could have other applications too. For example, he suggests, cities might embed computer chips with wireless capabilities into all of their streetlights. That would allow more efficient power usage (with motion sensors, they could be programmed to only turn on when a human being was nearby) and better management (a streetlamp could automatically notify city hall if it malfunctioned).

No standards yet

Still, we're nowhere close to having a standard platform to allow people to manage swarms of smart devices in one place. Startups like Berg and Thingsquare help companies building smart devices to connect them to the web. But we're nowhere close to having universal standards that would let all smart lightbulbs work together the way our PCs and smartphones do today.

It's the continuation of a trend: software will be increasingly central to our lives

There's a chicken-and-egg problem that will take time to overcome: it only makes sense to have shared standards for connected devices when there are enough of them in peoples' homes that it's a hassle to manage them individually. Yet users are less likely to buy a lot of devices if setting them all up is a hassle.

But markets eventually overcome these difficulties. Setting up a PC used to be hugely inconvenient, too. And when shared standards and user-friendly interfaces are created, that's when the real magic will start happening.

Three years ago, the venture capitalist Marc Andreessen described how "software is eating the world." Software companies are revolutionizing industries as diverse as cars, agriculture, books, and petroleum. Cheap mobile devices have accelerated the process. Today, most of us have tossed out our film cameras, paper maps, dedicated GPS units, rotary telephones, and other single-use devices because software enables the smart phones in our pockets to replace them.

In one sense, the proliferation of tiny wireless chips will have the opposite effect: we'll buy a lot of new devices instead of consolidating of previously separate devices into one. But in another sense, it will be the continuation of a trend: software will be increasingly central to our lives.

Today, a software update can instantly improve how well our phones take pictures, give us directions, or keep us in touch with our friends and family. In a few years, a software update will be able to instantly change how we light our homes, prepare our meals, water our lawns, and even care for our loved ones.

Here are some examples of the internet-connected objects that could transform the way we light our homes, water our yards, care for the elderly, and more.

Nest Thermostat

This thermostat allows you to monitor and adjust your home's temperature from anywhere in the world and has a number of other smart features. Cost: $249. (Nest)

Nest Protect

The second Nest product, the Nest Protect, is a sophisticated smoke alarm that communicates with a smartphone app. Nest recently suspended sales of this product to deal with a defect. Cost: $129. (Nest)

Tado

This device is another connected thermostat. The associated app uses geolocation to automatically detect when the homeowner is away and lower the temperature in order to save heating costs. Cost: € 299 ($410). (Tado)

Rachio

Available in June, this device replaces old-fashioned sprinkler control systems. The device not only allows users to control their sprinkler systems from anywhere, it can also check the weather each day to decide whether the grass needs to be watered. Cost: $249. (Rachio)

Lockitron

Lockitron lets consumers lock and unlock their doors using their smartphones. The homeowner can grant multiple people — family members, guests, petsitters — access from anywhere in the world. Cost: $179. (Lockitron)

SmartSense Multi Sensor

In addition to detecting motion, the Smartsense Multi can also detect temperature, vibration, and orientation. A combination of several SmartSense sensors can work as an effective home security system. Cost: $49. (SmartThings)

hue

This lightbulb will allow you to bathe a room in any color of light you choose with your smartphone. Cost: $60. (Philips)

LIFX

This Wifi lightbulb also allows you to control your room's color with a smart phone, but it's a bit pricier. Cost: $99. (LIFX)

WeMo Light Switch

Created by Belkin, this light switch allows you to turn your lights on and off using your smartphone. It can also be programmed to automatically turn on or off at sunrise or sunset. Cost: $50. (Belkin)

WeMo Insight Switch

This Belkin device allows you to not only turn your devices on and off from anywhere, but also to monitor their energy usage. Cost: $60. (Belkin)

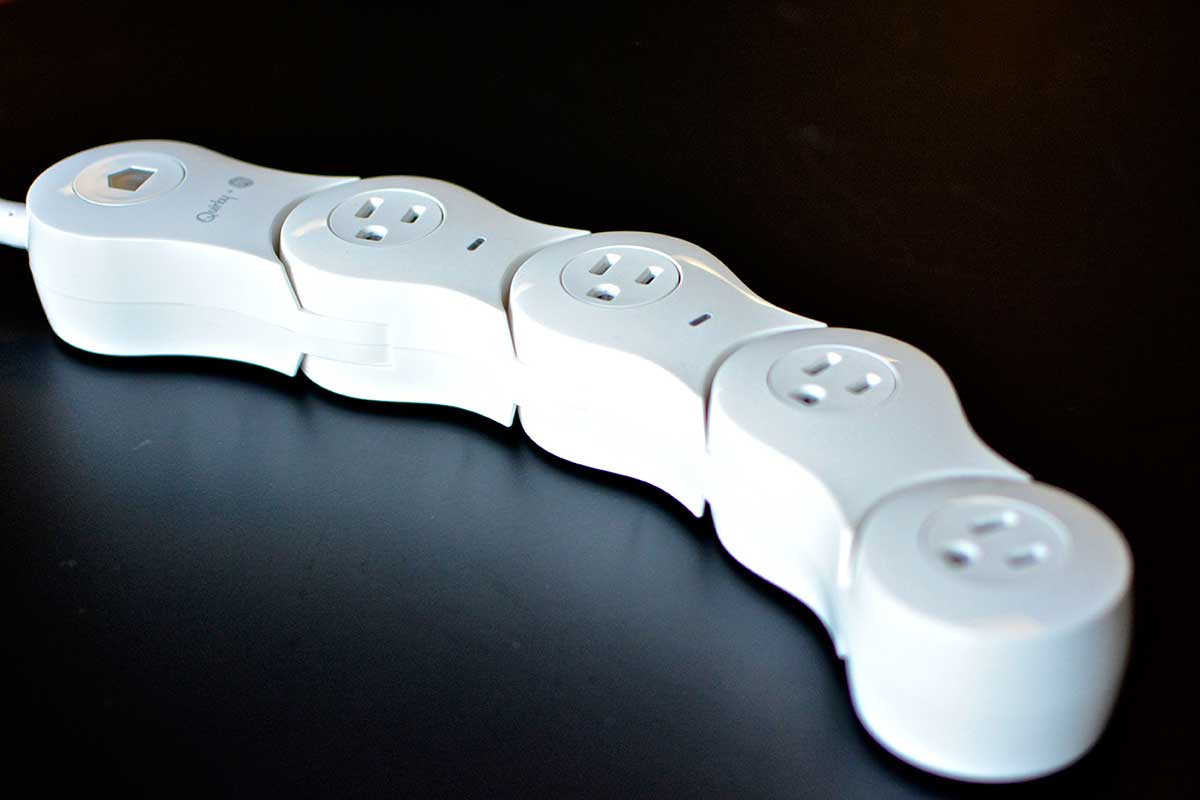

Pivot Power Genius

This internet-connected power strip allows users to turn on any device from anywhere in the world. Cost: $60. (Made by GE, a Vox.com sponsor.) (Electric imp)

Budweiser Red Light

This device keeps track of when the user's favorite hockey teams are playing. When the user's team scores, the light flashes and a horn sounds. Cost: $150. (Electric Imp)

Nimbus

This product is a "highly customizable 4-dial dashboard that tracks what’s important to you." The gauges can display temperature, traffic information, email notifications, or other information you care about. Cost: $100. (Note, this is a product of GE, a Vox sponsor) (Electric Imp)

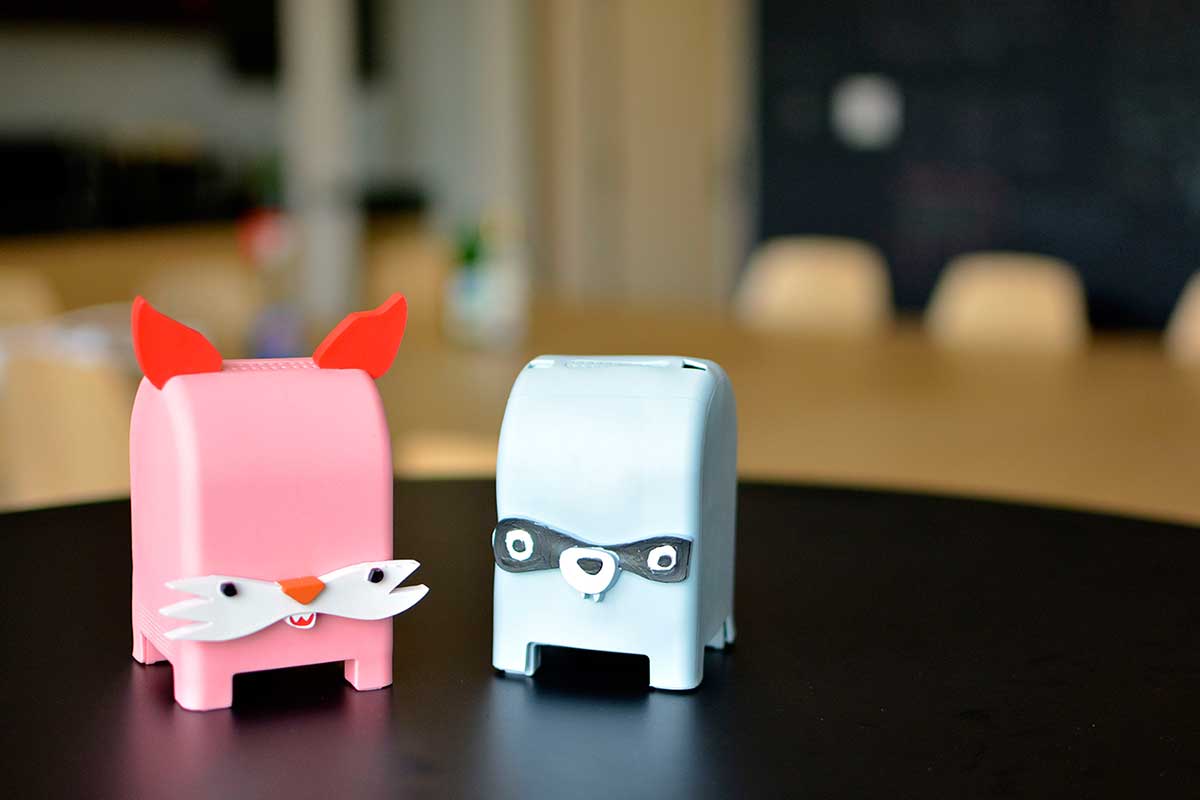

Toymail

These toys allow children to send and receive voice messages to friends and family anywhere in the world. Electric Imp co-founder Hugo Fiennes says his daughter uses one to send messages to her grandparents in the United Kingdom. Cost: $59. (Electric Imp)

Porkfolio

This "smart piggy bank that helps kids save" tracks how much money has been inserted. Kids can check their savings using a mobile app. Cost: $50. (Electric Imp)

Little Printer

The Little Printer prints out messages sent to it via the internet. "Send a message or photo from anywhere in the world and your Little Printer will print it immediately," the company says. Cost: $199. (Berg Cloud Limited)

WeMo Crock Pot

Crock-Pot teamed up with WeMo to produce a slow-cooker that users can activate and monitor with their smartphones. It's scheduled for availability in the spring. Cost: $130. (Crock Pot)

Hiku

This device helps people maintain their shopping list. Users add items to the list by scanning barcodes or by dictating product names into the microphone. The list is accessed from a smartphone. Cost: $79. (Electric Imp)

SaferAging emergency button

Pressing this button initiates a voice call to a care provider. Cost: $50 to $150, depending on model. (SaferAging)

Editor: Eleanor Barkhorn

Designer: Uy Tieu

Developer: Yuri Victor

Illustrator: Dylan Lathrop

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/32449799/internet_of_things_cover.0.jpg)